Vibrio Saga, Part I — Atlantic Oysters in a Warming World

This post can also be found on the Environmental Change and Aquatic Biomonitoring (ECAB) Lab website.

Science can often be portrayed as cold and formulaic, and this perception is not entirely without merit. Sometimes, though, science unfolds like a novel, with characters coming and going, acting out a plot with twists and turns, weaving an engaging narrative.

In the late summer of 2022, I visited an oyster farm in Nova Scotia, looking to buy oysters as the culinary treat they are. It was Labour Day weekend, and this was the first weekend the farm had been open all summer, because the levels of a bacterium, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, had been too high for the farm to sell oysters. I went home and immediately looked for anything I could find on this bacterium in Atlantic Canada, if it had been a regular problem in recent years, and came up with nothing at all. This is how my quest to understand Vibrio began.

A Crash Course in Vibrio

Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Vp) is a species of bacteria that normally lives in warm, brackish or estuarine waters around the world. It is the archetypal villain of the story and has been known to cause foodborne illness from seafood since the 1950s.1 When infected seafood is consumed raw or undercooked, there is a risk for Vp illness. Bivalve mollusks such as clams, mussels, and oysters are constantly filtering water through gills, acquiring food. Vp doesn’t pose as much of a threat when in clams or mussels, because in this part of the world, clams and mussels are often eaten cooked, killing the bacteria, whereas oysters are often eaten raw. Bivalve mollusks are not so much the culprit here, but more an innocent bystander in a wider problem. Since the early 2000s, infections by Vp from raw oysters have been recognized as a human health problem in both Atlantic and Pacific Canada.2 Enter stage left the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), an institution that holds a great deal of responsibility for public health. The CFIA regularly tests oysters in Atlantic and Pacific waters for Vp to make sure they are safe for humans to consume, as stipulated by the CFIA’s own Shellfish Sanitation Program Manual.

Image: PEI Seafood. PEI oysters are world-renowned. Here they are featured in Vogue magazine.

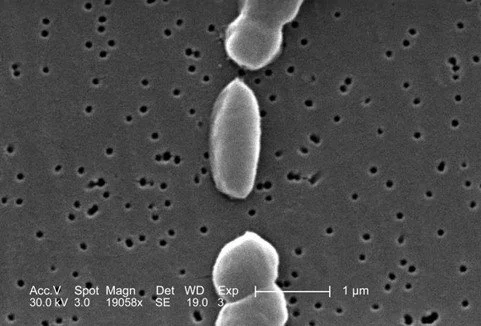

Infection by Vp is rare, but serious. Vp and its villainous friends in the genus Vibrio are some of the most notorious marine pathogens throughout history; its relative, Vibrio cholerae, is the bacterium that causes cholera. Fortunately, we know that not all Vp is the same. Some strains of Vp — ones that make two proteins, tdh and trh — are more likely to cause illness.3 The method CFIA currently uses to test for Vibrio in oysters does not account for this, so there are records of the amount of Vp, but not measures of the ability of that Vp to cause illness.4 Of course, wherever there is more Vp, there is greater risk for illness.

While Vp is recognized as a threat to human health, not much is known about Vp in Atlantic Canadian waters: where it occurs, when outbreaks could happen, and its basic interactions with its environment.5 Much like the literary villain, it is shrouded in mystery. Looking back through CFIA testing records can help us answer a lot of these questions. Because Vp comes from the water, and it is natural to find there, there is little that oyster growers can do to get rid of it once it shows up, besides waiting for cooler environmental conditions, when Vp becomes less abundant. Even then, it can take days for Vp counts to return to where they were before high water temperatures.6 The CFIA recommends either resubmerging oysters or placing them in cold water for storage to speed up this process but neither is quick.7 Not only is it important to understand the state of Vp for the sake of consumers, who might be made sick by unsafe oysters, it is also important for oyster farmers and policy makers to understand the state of Vp in the Atlantic region, and how that might be changing. If oysters fail food safety guidelines, they cannot be sold, and this means a financial loss to farmers. Policy guidelines must be careful to ensure food safety for consumers and financial viability for oyster growers, who both lose out if Vp counts are too high.

Image: Janice Haney Carr through the CDC’s Public Health Image Library. Vibrio parahaemolyticus as seen under a scanning electron microscope.

It is apparent that Vp is already a problem and will continue to be so into the future.8 Vp grows best when the waters are warm in the summer. Unfortunately, this is also when many people like to eat oysters. Vp is one of the fastest growing marine or estuarine bacteria and will double its population in a matter of hours at typical summer temperatures. This is why it is important that oysters be regularly monitored for Vp. Concerningly, Vp is showing up more often, and this is thought to be because of warming marine temperatures. It is showing up earlier in the season, staying for longer, and is causing oysters to fail food safety tests during the hottest months of the year when oysters are in demand. It is important to understand how Vp acts right now in order to be able to predict what might happen in the future. Vp lives on the surface of organic matter in the water, and there is evidence that it can survive cold winters by living in the sediment at the ocean floor. There is increasingly no need for Vp to hide in the marine sediments, because the water isn’t getting cold enough in the winter, and the strains of Vp in the Atlantic Canada region appear well-adapted to water temperatures down to at least 4°C.9

Although Vp comes from the water, and that means it can show up in oysters all around Atlantic Canada, it seems to show up more often and in higher numbers in different places. While sea surface temperatures are an important factor in knowing where Vp could exist, there are more environmental factors that can influence Vp abundance: salinity, pH, and organic matter in the water can all contribute to higher abundances of Vp.10 There is a hope that, with a good idea of how Vp acts when all of these factors vary, we might be able to get a general idea of the state of Vp in Atlantic Canada.

Image: Choose PEI. An estuary in PEI, seen from the air. Estuaries such as this one provide ideal habitat for oysters and Vp alike.

Much of the current knowledge about Vp in North America comes from studies in the United States, which concludes that the fastest growth occurs in warm water. Vp in Atlantic Canadian waters is not the same as Vp in Atlantic waters of the US, though. The quest to extend the knowledge of how Vp acts in the environment from warmer American waters to colder Canadian waters is challenging, but rewarding, and it is a complex problem that I have been working on for nearly two years. It began as a personal interest project, but now forms the basis of my summer research in the ECAB Lab. Over the next year, I look forward to studying Vp as my BSc Hons. degree in Environmental Science.

Notes

1^. This seminal paper by Kaneko and Colwell in 1973 touches on outbreaks in Japan.

2^. It is difficult to pinpoint an exact year, because it’s hard to know what programs or departments may have looked into the issue and when. The guidelines were most recently updated after a 2015 outbreak.

3^. Described briefly with reference to Atlantic Canada in this paper by Banerjee and Farber.

4^. This is not explicitly mentioned in the Shellfish Sanitation Program Manual, but it is apparent from the description of methods found in Health Canada’s archives.

5^. For what is previously known, see Banerjee et al. (2017) and Ferchichi et al. (2018).

6^. Fernandez-Piquer et al. (2011) find a 2.5 log10 CFU/g reduction in Vp counts in Pacific oysters only after 18 days of storage at 3.6°C.

7^. In Measures to control the risk of Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Vp) in live oysters.

8^. Ferchichi et al. (2018) predict generally worsening Vibrio risk with worsening climate change impacts.

9^. In Jennifer Martin-Kearley’s 1992 master’s thesis, growth at 4°C is a defining characteristic of some Vibrio species off the coast of Newfoundland (p. 118). Vezzulli et al. (2016) note that Vibrios are adapted to colder waters in e.g. Nova Scotia, and these populations respond more readily to warming water temperatures.

10^. Namadi and Deng (2023) have used these parameters in modelling Vp counts at two sites in North Carolina and New Hampshire, USA.